For Sale: 2nd Generation Colt Navy

Price $16000

Genuine Colt, not a reproduction. Serial #1637

Includes the Wood case and the accessories and a Certificate of engraving by Mark Hoechst

For more photos, click on the Colt photo or GALLERY button.

If you are interested, email me and I will send you higher resolution photos.

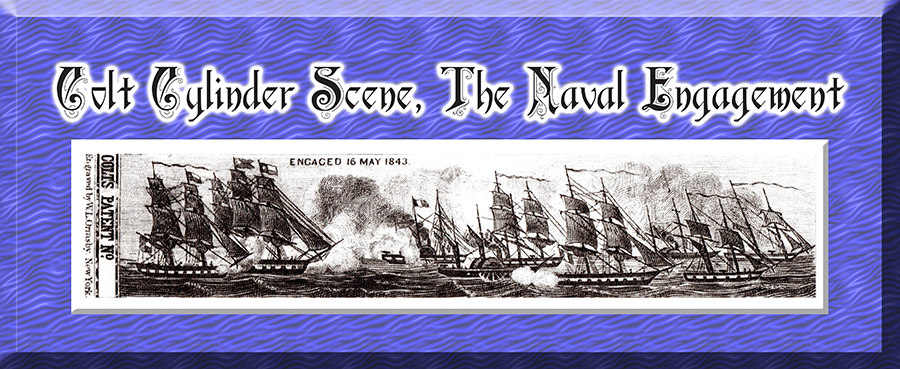

Colt Cylinder Scene The Naval Engagement

2nd Generation Navy C series Colt

Engraving, the finish: rust blue, gold plating and the resin-ivory with Shreger Lines grips done by Mark Hoechst.

The Engraving of the Navy Colt

Illustrating the elements of the Navel battle fought in the Gulf of Mexico from April 30th to May 16th, 1843. The Captain Edwin Moore, the ship Austin and a map of the Republic of Texas are incorporated in the theme of the cylinder scene.

The following information is from Arthur Tobias book Colt Cylinder Scenes 1847-1851

The Engagement, the Background of the battle:

Steam powered ships and new long-range exploding shells that were just emerging demanded armored ships. The future of the infant Texas Republic was hanging on by a thread in 1843. Reelected 3rd President of the Republic, Sam Houston believed that his weak, seriously threatened nation would garner the sympathies of the U.S. and force the issue of statehood. Houston hated Edwin Moore, the Commodore of the Texas navy who agreed to Texas's second President Mirabeau Buonaparte Lamar's request to command the new fleet of ships. Moore barely escaped prosecution when he resigned his U.S. naval commission in July of 1839. Houston strangled the financial lifeline that sustained the navy. Moore threw himself heart, soul and pocketbook into the cause of Texas. After Moore was ordered to return his ships to Galveston and give up his command, he instead headed out on the treacherous Gulf waters.

The Battle

On April 30th, he was in Campeche with his two ships, the Austin and Wharton when they attacked two Mexican steamers and three sailing ships. At 9 a.m. the wind dropped, and Moore’s sails drooped. For two hours the Mexican steamers did not attack even though Moore’s ships were dead in the water. When they did attack, a fresh breeze filled Moore’s sails and they were able to rout the modern navy. In Campeche, Moore and his men were welcomed by ecstatic throngs. The mayor of Campeche gave much needed long-range cannons from his fortifications to the Texans ships. On May 16 Moore’s two ships with six smaller ships sailed out of the harbor at dawn. On the Mexican side, three steamers, two armed brigs and three schooners moved into the fray. At 10:00 a.m. with the Austin and Wharton within three miles of the Mexican navy the wind died. By 11:00 the wind picked enough to engage, soon the Wharton fell behind on the vagaries of the breeze.

Alone the Austin sailed on, chasing, and engaging the two Mexican steamers. A large hole near the water line forced Moore to call off the attack. Two sailors had been lost on board the Wharton in a gunnery accident. Moore’s Austin had three killed and twenty-two wounded. On the other side, had eighty-seven killed and one-hundred-sixteen wounded. It was the first instance of the use of exploding shells, used by the Mexicans, in naval combat and the last time sail would defeat steam. At no time had the Texans and the Mexicans closed to less than 1 ¾ miles. Never close enough to use the Colt revolvers and carbines on board.

With sincere thanks to Arhur Tobias for permission to gleam from his book Colt cylinder Scenes 1847-1851 for the above information. Reading the book, I learned that Sam Colt wanted to protect his patent rights. From the book, “The unique, inimitable Ormsby engravings on every Colt pistol cylinder promised a visible means of guaranteeing the buyer that he or she was receiving a genuine product.” So, learning why the cylinders were engraved, now we know what was “The Naval Engagement Scene” was about.